The SR-71 with Detachment 4 At R.A.F. Mildenhall

by Bob Archer

SR-71A 61-7973 fly past. Photo by Bob Archer

SR-71A 61-7973 fly past. Photo by Bob Archer SR-71A 61-7960. Photo by Bob Archer

SR-71A 61-7960. Photo by Bob Archer Twenty five years ago the US Air Force withdrew funding for the SR-71 programme. The lack of budget effectively eliminated the programme worldwide, including the two aircraft located at R.A.F. Mildenhall. Despite the uniqueness of the intelligence captured on the sophisticated sensors, the programme was incredibly expensive, consuming millions of US dollars annually in operating costs. So expensive in fact, that the senior officials with their hands on the financial tiller sought to axe the programme in favour of more glamorous fighter budgets. Despite attempts by politicians to restore the SR-71 to active duty, eventually the type was “killed off” by a Presidential mandate. Thus ended a quarter century of aviation history performed by a truly exceptional aircraft.

The Lockheed SR-71 was a familiar sight above the skies of Eastern England for almost 16 years. Operating from Mildenhall, the small detachment was one of just three locations worldwide which regularly hosted this spectacular aircraft. Air Force crews associated with the programme applied the nickname "Habu," after a deadly poisonous snake which inhabited the island of Okinawa. The general public in the Mildenhall area preferred the term "Blackbird" as it was something which most were more familiar with. The SR-71 programme was officially known as "Senior Crown" for budgetary purposes, although the name was not widely known outside corridors of power. The appearance of the first SR-71 in the United Kingdom was as widely publicised, as was its departure from service 16 years later. In between times, the SR-71 was a significant part of aviation in East Anglia, although all aspects of operations were shrouded in a veil of secrecy.

The SR-71 was an aircraft of superlatives, and was in fact one of the most un-stealthiest of designs, producing huge radar signatures on the Federal Aviation Agencies long-range radars. Due to the extreme heat from the exhaust plume controllers could easily track an SR-71 at ranges of several hundred miles when flown at its operational altitude and speed. The Soviet Union tried to send interceptors within parameters, although none of their air-to-air missiles were ever fired, as the SR-71 was so fast, when cruising at Mach 3+, that no missile would have been able to have caught up! [

with the exception of R-33 (AA-9 Amos) missile that can fly Mach 4.5 - ed.] Only a lucky strike could have brought down an SR-71, and none ever did.

Despite high levels of secrecy surrounding the programme, operations from Mildenhall were fairly predictable as there were many familiar tell-tale sights and sounds of a typical SR-71 departure:

• The early departure of dedicated KC-135Q tankers

• The commencement of each SR-71 mission precisely on the hour

• The earth-shattering roar from the Pratt and Whitney J58 engines producing a massive 32,500 lbs of static thrust each

SR-71 61-7958. Photo by Bob Archer

SR-71 61-7958. Photo by Bob ArcherMany missions were four or five hours duration, and therefore the casual observer did not have to possess the mind of Einstein to work out an approximate time of return. All too often, an 08.00 departure signified a return five or so hours later. This was not always the case, but many times the SR-71 would land back at Mildenhall around 13.00 - perfect timing for the astute photographer, particularly if the pilot and RSO were happy to perform an overshoot at the completion of a training mission. Ground support technicians much preferred to be able to work on the aircraft which had cooled slightly, which an overshoot helped to produce. At altitude, the external surfaces of the SR-71 heated up significantly, often reaching temperatures of 316° centigrade (600° Fahrenheit,) resulting in the titanium metal used in its construction retaining some of this heat once back on the ground.

Measuring 107 feet (32.6 metres) in length, the SR-71 was an extremely long, thin aircraft, with its two huge Pratt and Whitney J-58 axial-flow turbojets, each producing 32,500 pounds of thrust (145 kN), buried inside their blended nacelles, spoiling an otherwise perfect delta-wing design. Pratt and Whitney engineers, working in conjunction with Lockheed's Skunk Works personnel, conducted studies, and determined that less than 20 percent of the total thrust needed to fly at Mach 3 was produced by the basic engine itself. The remainder was the product of the unique design of the engine inlet and "moveable spike" system at the front of the engine nacelles, and by the ejector nozzles at the exhaust which burn air compressed in the engine bypass system. The result was an extremely noisy aircraft, especially on takeoff, and one whose reheat signature produced a distinctive set of diamond pattern shock waves. Total weight of the aircraft for a mission was usually in excess of 50 tons, of which almost 40 per cent was JP7 fuel. Despite the terrific power produced by the engines in reheat, the SR-71 was reluctant to depart the runway until several thousand feet of concrete had passed beneath the sleek fuselage. Almost as soon as the aircraft had become airborne, the pilot would bank slightly to starboard, offering a wonderful view of the diamond shock waves. Within minutes the massive engines had propelled the aircraft into the sky to rendezvous with its first tanker over Lincolnshire, at the start of another classified reconnaissance sortie.

The SR-71 was clearly an aircraft whose advanced design was of monumental proportions, breaking new ground in aeronautical innovation in virtually every aspect. Kelly Johnson, the then head of the legendary Skunk Works, managed to develop technological innovation in aeronautical design which computers of the 21st century would find challenging. Even today, no air arm has an aircraft type to match the SR-71, which was a child of the late 1950s. Most remarkable of all was the commitment to have the new aircraft flying in just twenty months.

First Operational Delivery

Взлет SR-71 61-7971. Photo by Bob Archer

Взлет SR-71 61-7971. Photo by Bob ArcherThe first SR-71A was delivered to Beale AFB, California on 10 May 1966, with operational sorties for the USAF beginning on 21 March 1968. The 4200th Strategic Wing operated the type until 25 June 1966, when many of the four digit unit designations were replaced. In its place, the 9th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing was reformed as the primary reconnaissance unit in residence.

SR-71s were forward deployed to Kadena AB, Okinawa, for operations over North Vietnam, and to monitor other potentially hostile nations in South East Asia. Detachment 1, of the 9th SRW was formed at Kadena to control the activities of the deployed Blackbirds. Initially the SR-71 was a total stranger to Europe. The first trans Atlantic mission was in October 1973 during the Yom Kippur War, when an SR-71A flew from Griffiss AFB, New York to monitor Egyptian, Jordanian, and Syrian troop locations, enabling ally Israel to adjust her forces tactics and win the campaign. The missions highlighted the need for the US to be able to utilise air-bases in Europe as forward operating locations for reconnaissance sorties.

Initially SAC wished to operate a small SR-71 detachment at Torrejon AB, Spain, although the Spanish government refused to allow overt reconnaissance to be performed from their country. Furthermore the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD) refused to permit SR-71 operations at Mildenhall in October 1973 during the Yom Kippur War, worrying that support for the United States might inflame Arab nations and disrupt oil supplies.

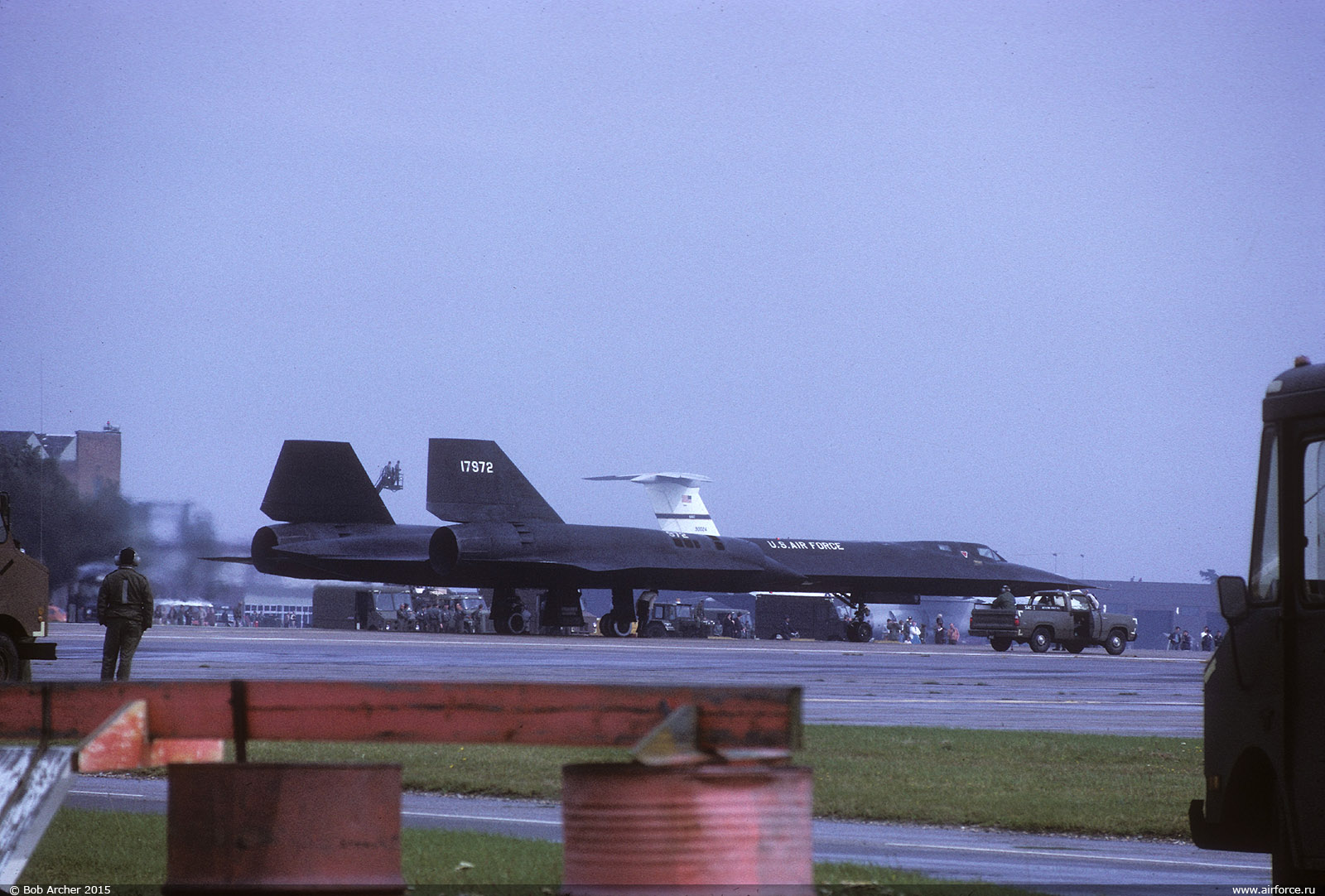

Negotiations between the United States and the British MoD for an "occasional" operating base in the United Kingdom were finally agreed in principal during 1974. However the feasibility of such operations still needed to be evaluated. The US decided to send an aircraft to England, but to enable the operation to raise little suspicion as to the true nature of the visit, the flight was to be staged under the full glare of publicity. The two trans-Atlantic legs were flown to enable the SR-71 crews to capture the fastest crossing time - between New York and London for the outward sortie, and the distance from London to Los Angeles for the homeward section. On 1 September 1974 Majors James V. Sullivan, pilot, and Noel F. Widdifield, reconnaissance systems officer (RSO), crossed the starting line in 61-7972 above New York at approximately 80,000 feet and speed in excess of 2,000 miles per hour. Exactly 1 hour 54 minutes and 56.4 seconds later, they had set a new trans-Atlantic world speed record. The average speed was 1,817 mph over the 3,488-mile course, slowing to refuel just once from a Boeing KC-135Q Stratotanker. The aircraft landed at Farnborough, where it was the prime static display exhibit at the bi-annual SBAC event. It marked the first time the secret plane had been on public display outside of the United States. Another historic speed record was set on the return journey, when Capt Harold B. Adams, pilot, and RSO Major William Machorek, flew from London to Los Angeles. The distance was 5,645 miles in a time of 3 hours 47 minutes and 39 seconds for an average speed of 1,480 miles per hour. The difference in the two speed records was due to refuelling requirements, and having to reduce speed over major US cities. Despite precautions, a large number of people in the Los Angeles area reported broken windows due to the sonic boom. The aircraft arrived almost four hours before its departure from London, due to the eight-hour time difference between the UK and California. The departure airfield in the UK was RAF Mildenhall, which enabled 9th SRW personnel to conduct an unhindered evaluation.

SR-71 61-7962. Photo by Bob Archer

SR-71 61-7962. Photo by Bob ArcherEven more important than the record flights, was the success of the feasibility study into operations from RAF Mildenhall. The US notified the MoD that it would like to begin operations on an ad hoc basis. The MoD approved the request in principal, with the proviso that operations be restricted to a maximum of 20 days in duration, and ministerial approval was required for each visit. Initially, SR-71 sorties were rare, and generally only lasted a few days. The first SR-71 deployment to Mildenhall began when 61-7972 returned on 20 April 1976 for a ten-day stay. The station also housed a single U-2R operation at the time, with the aircraft being hangared on the south side of the airfield (normally as soon as it landed, to enable its' precious film to be extracted from the cameras). The assignment of an occasional SR-71 deployment was kept separate, although the two aircraft were operated from the same area. The U-2R needed no aerial support, as its glider-like capabilities enabled ten-hour sorties to be flown with ease. The SR-71, however, required the presence of several KC-135Q tankers, which carried the special JP7 fuel, unique to the "Blackbird." The 17th Bomb Wing operated the KC-135Qs at Beale AFB during 1975 and 1976, until these were reassigned to the 100th ARW in September 1976.

Thus far tasking had been in support of NATO exercises in Europe or to evaluate operations from Mildenhall. The first dedicated operational strategic reconnaissance deployment began in May 1977 when 61-7958 was flown to Mildenhall. The historic first mission took place on 20 May, to satisfy a Navy request for high resolution radar imagery and electronic intelligence sensor recording of the submarine bases in the Murmansk area. The mission was a joint effort with 55th SRW RC-135V Rivet Joint 64-14846, which also flew from Mildenhall. The Top Secret joint mission was likely to have been flown to enable the SR-71 to capture all manner of "emitter" traffic across the airwaves produced to monitor the Rivet Joint, and vice versa!

Tasking of SR-71 missions was approved at the highest level of government, with locations of primary interest being situated behind the Iron Curtain, in particular East Germany, and of course the Soviet Union. One area which was frequently the subject of interest was the southern Barents Sea around the Kola Peninsula, particularly around the Murmansk Oblast. Whereas the SR-71 had overflown North Vietnam to obtain data, overflights could not take place above eastern European countries or Russia. Therefore SR-71 missions were restricted to observing activities from the periphery over international waters, or friendly territory. Nine visits took place during the 1970s, although as the decade drew to a close, the need for additional, lengthier stays began to become apparent. 61-7979 departed Mildenhall for home on 2 May 1979, the day before the Labour government was swept from power, and Margaret Thatcher became the new Prime Minister. The new administration was more amenable towards the US extending the UK SR-71 operation, although initially this was undertaken on a gradual basis. The final deployment of 1979 was by 61-7976, which arrived on 18 October and stayed for 26 days.

Detachment 4 Formed

SR-71 61-7962. Photo by Bob Archer

SR-71 61-7962. Photo by Bob ArcherAhead of this symbolic deployment, Detachment 4 of the 9th SRW was formed at Mildenhall on 31 March 1979. The unit became responsible for the ongoing U-2R operation, with one aircraft almost permanently in residence, as well as the occasional SR-71 presence. The SR-71 operation was known as Giant Reach.

Throughout 1980, the duration of SR-71 deployments lengthened, and by the end of the year, the Detachment was virtually operating the type full time. This increased even more during 1981, and on 5 April 1982 the Ministry of Defence received Prime Ministerial approval to allow Detachment 4 to operate on a permanent basis with two SR-71s assigned. However, the MoD still retained the final approval of the more sensitive missions. The aircraft continued to operate from the hangar complex on the south side, but it became apparent that a permanent, more suitable pair of structures would need to be constructed. Work on these began in 1985, with 61-7962 having the honour of christening the new complex upon returning from a mission on 8 August.

Whereas the United Kingdom was the SR-71s primary operating base in Europe, the extremely changeable, and sometimes unpredictable weather conditions called for a number of alternate locations to be established. SR-71 operations frequently took the aircraft above the Baltic Sea, and around the top of Norway into the cold arctic region to monitor military complexes in northern Russia. Therefore the US approached the Norwegian government, who agreed in principal that in an emergency, their bases could be used. The first occasion when an aircraft diverted was on 13 August 1981 when 61-7964 landed at Bodo, while on a combined mission/delivery to RAF Mildenhall from Beale AFB. The aircraft suffered an oil malfunction in one of the engines. Rather than risk flying the sick aircraft to Mildenhall, the crew elected to divert to Bodo.

The unexpected diversion resulted in a KC-135Q being hastily dispatched from Beale AFB. The tanker full of technicians and spare parts arrived at Bodo, above the Arctic Circle, around 07.00. Rectification work commenced immediately and continued until late into the night. With no hangar available, ‘964 was left outside, which was a new experience for the California based personnel. The technicians were back at work at dawn the following day, and eventually restarted one engine, although the other refused to fire. With little fuel remaining in the SR-71 tanks, the orbiting KC-135Q, which had launched from Mildenhall to assist with the final leg of the journey, elected to land at Bodo. The overweight tanker ran off the runway, sank into the asphalt and had to be pulled out. Eventually both SR-71 engines started, and preparations were made for departure, but not before the name “Bodonian Express” and a small white crab were applied to the tail.

SR-71 61-7964 "Bodonian Express". Photo by Bob Archer

SR-71 61-7964 "Bodonian Express". Photo by Bob ArcherDetachment 4 increased to two aircraft from 19 December 1982 when 61-7971 arrived to join 61-7972. With two aircraft stationed in England, the US Air Force began to undertake many more missions and expand its area of interest with additional peripheral photography of Eastern Europe, and the Middle East. This enabled the planners to increase the number of sorties flown with a corresponding expansion in the quantity of intelligence obtained. Understandably the aircraft could not fly supersonic overland, as the shock wave would have created catastrophic damage. However, missions over water could be accomplished at the design cruise normal speed of Mach 3+. Although secrecy at the time prevented details from emerging, subsequent releases have highlighted that many sorties to the militarised region of northwest Russia were on behalf of the U.S. Navy. The subsequent release of formerly classified documents has confirmed that the SR-71 frequently flew to an area off the coast of Murmansk to obtain details of the submarine activity with the Soviet Northern Fleet. The strategic submarine base at Gadzhiyevo, and the Northern Machine-Building Production Association facility at Severodvinsk in particular were of primary interest. The Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral James L. Holloway III requested regular SR-71 sorties to region, having highlighted five naval bases of particular interest. There were Gadzhiyevo, Gremikha (now known as Ostrovnoy), Severomorosk, Vidyayevo, and Zapadnya Litsa, which between them housed the Northern Fleet, which controlled the lion's share of Russia's nuclear submarine force.

On 9 July 1983, SR-71A 61-7962 settled onto the runway at Mildenhall after a lengthy ferry flight from Beale AFB. To the casual observer, this was just another SR-71, and unlikely to cause too much excitement, as the same aircraft had been deployed here previously, having spent more than two weeks deployed at Mildenhall during September 1976. Except that this was a clever subterfuge, as it was not '962. The aircraft was in fact 61-7955, the Palmdale based Lockheed test aircraft, which was evaluating the new Goodyear Advanced Synthetic Aperture Radar System (ASARS-1). The decision to apply a different serial for the duration of the stay in England, was taken to mask the true purpose of the test aircraft flying a rare operational mission overseas. The subterfuge worked, and the full details stayed buried for more than a decade! 17955 stayed long enough to complete the evaluation, before returning home, and reverting to its true identity. The operational evaluation performed as required, and the ASARS-1 was subsequently installed for specific missions.

Operation El Dorado Canyon

SR-71 61-7964. Photo by Bob Archer

SR-71 61-7964. Photo by Bob ArcherThe belligerent sabre-rattling by Colonel Mumar Ghadaffi of Libya increased as he ordered his military forces to become more aggressive to non-Muslin governments, in particular, the United States. This was coupled with his financial support and backing for terrorist groups, resulting in his regime becoming a thorn in side of Washington. Confrontation seemed the only solution to silence the unpredictable figure-head. A build-up of tanker aircraft at RAF Fairford and Mildenhall heralded the likelihood of an air strike, and on the evening of 15 April 1986, the 20th and 48th Tactical Fighter Wings launched EF-111As and F-111Fs respectively, from RAF Upper Heyford and Lakenheath. The latter were used to strike targets in Libya while the "Spark-Varks" provided electronic jamming. Named Operation El Dorado Canyon, the mission was fairly successful as had the effect of silencing the vociferous Colonel. Post strike photography was carried out by the two Mildenhall-based SR-71s, with both aircraft being airborne simultaneously. A dual mission was flown on 16 April and the two following days, as cloud cover hampered an effective take until the third occasion. Images captured on film were taken from the aircraft and processed before being loaded aboard C-135C 61-2669, which was the aircraft assigned to the USAF Chief of Staff. The imagery was deemed of such importance that the Chief of Staff himself, General Charles Gabriel, accompanied the film from Mildenhall back to Washington for analysis. This was the only occasion when Det 4 flew both its aircraft together operationally.

Not all sorties went smoothly. On 24 May 1987, the pilot of 61-7973 managed to overstress the aircraft while on a mission. The aircraft recovered safely to Mildenhall, but inspection by technicians subsequently determined that temporary repairs would need to be carried out to enable a flight back to Palmdale for further analysis. The aircraft returned to the USA on 22 July, although the likelihood of the programme being terminated, may well have been the reason for expensive rectification work not proceeding. The aircraft remained stored with Lockheed at Palmdale subsequently, before being placed on display in the Blackbird Airpark.

SR-71 61-7964 appears to have liked Norway. Having been the first to divert there in August 1981, the aircraft had the honour of visiting the country twice more while on operations. On 6 March 1987, ‘964 suffered a technical problem, requiring the crew to divert, and three months later, on 29 June the SR-71 crew landed in Norway again. The March visit obviously caused the technicians some extensive problems, as the SR-71 was stranded in Norway for around 14 days. The second diversion, must have been considerably more straight forward to rectify, as 61-7964 flew back to Mildenhall three days later.

SR-71 61-7980. Photo by Bob Archer

SR-71 61-7980. Photo by Bob ArcherDetachment 4 was never short of missions. The Middle East was periodically the target area, following tension between certain nations. Missions to the region were launched from Kadena as well as from Detachment 4. The French government characteristically refused authority to overfly their territory, resulting in SR-71 missions from Mildenhall being routed around the Iberian Peninsula. One noteworthy sortie was performed during early March 1979 to monitor the situation between the Republic of Yemen and her Saudi Arabian neighbour. The Yemenis appeared to be on the brink of invading Saudi territory, with the U.S. authorities anxious to gain intelligence on the intentions of the Yemeni government. Faithful SR-71A 61-7972 was dispatched to RAF Mildenhall to perform the lengthy sortie. After two cancelled missions, 17972 was airborne before dawn on day three, and completed the tanker rendezvous before streaking into the sunrise across the Mediterranean Sea. Two more mid-air refuellings were accomplished before ‘972 headed for the target area. A glitch in the automated navigation system resulted in the aircraft accidentally overflying the planned turn point, as the optical bar camera in the nose, and the various individual cameras in the chine bays captured their imagery. The delay in completing the turn produced unexpected results, yielding much valuable additional data. The crew returned the aircraft to Mildenhall after completing a mission lasting ten hours.

Sorties such as this were fairly uncommon, as most were conducted to gather intelligence from the old adversary, the Soviet Union, and her Warsaw Pact allies. Missions frequently involved the SR-71 departing Mildenhall and flying north around Norway before seeking activities in the Barents Sea and White Sea areas. Others involved the SR-71 overflying the Baltic Sea to look deep into Poland, East Germany, and Russia. Sub-sonic missions along the border between the two Germanys were also carried out.

It was clear that the SR-71 was an extremely flexible reconnaissance platform, even though it was hugely expensive to operate. Furthermore many senior Air Force planners in the Pentagon were from the "fighter community," and were largely ignorant of the precise capabilities of the SR-71. Some wanted the SR-71 to be killed off to save money, which, they argued, could be better spent on more lucrative programmes. One officer stands out, head and shoulders above all others, in maintaining the SR-71 programme. General Jerry O'Malley, who had been an RSO with the 9th SRW earlier in his career, was one of the most staunch supporters of the SR-71, as he clearly knew the capabilities and value of the Blackbird. He became Commander of Tactical Air Command, and was widely tipped to become Air Force Chief of Staff. However, tragedy struck on 20 April 1985, when the North American T-39 Sabreliner carrying General O'Malley crashed at Wiles-Barre airfield in Western Pennsylvania, killing all on board. Without guidance from the General, the Senior Crown programme began to see the end in sight. General Larry Welch, the Commander in Chief of SAC eventually became the Chief of Staff, and set about eliminating the SR-71 from service. It was ironic that the single most vociferous opponent of Senior Crown had also been the head of SAC, its’ operating command, and therefore was more aware than most of its unique capabilities.

Farewell

The 1 October 1989, the first day of fiscal year 1990, the Air Force issued an order suspending all SR-71 operations, except for proficiency flights. On 22 November 1989, all USAF SR-71 operations were terminated. Those at Detachment 4 had ceased flying two days earlier when 61-7967 had flown the last training sortie. The aircraft was fitted with an optical bar camera, which was uncommon at Mildenhall. The crew must have been aware that this was likely to be their last sortie for a while, as they performed several overshoots before settling the giant aircraft onto the runway for the last time. The two jets remained securely tucked away in their barns for the next few weeks, while final plans were made for the Detachment to return the aircraft to the USA, and inactivate. On 16 January 1990 both aircraft flew a functional check flight to ensure all systems were working correctly.

Экипаж SR-71. Photo by Bob Archer

Экипаж SR-71. Photo by Bob ArcherTwo days later the press were admitted to watch first hand as the Lockheed technicians prepared 61-7964 for the journey home. Access to the barns was available to all, with the two crew members, Major Tom McCleary (pilot) and Lt. Col. Stan Gudmundson (RSO) freely chatting to the media. Shortly before lunchtime the aircraft spooled into life, and with all systems functioning normally, taxied to the runway for the last time. With the characteristic roar, and the diamond shock waves dancing in the clear winter air, the SR-71 gracefully lifted from the runway and flew a 360 degree pattern to perform a fast, very low fly-by, before the pilot pointed the nose skyward and headed for Beale AFB. Next day 61-7967 departed, with much less fanfare. The departure was the end of an era. Similar activities were conducted by Detachment 1 at Kadena AB, Okinawa, with their two jets also flying back to the USA. On 26 January 1990 an SR-71 decommissioning ceremony was staged at Beale AFB, with General Welch, the main architect of the type’s demise, being in attendance.

Detachment 4 flew 894 operational missions, with a further 164 being functional, test, or delivery flights. SR-71A 61-7960 had the honour of performing the most operational missions, completing a total of 342. This aircraft spent 15 months assigned to Detachment 4 from late 1985 until early in 1987. Throughout the period, sorties were flown above or near to many locations to gather intelligence vital to the US government and NATO.

The SR-71 had obtained significant intelligence data during its 25 years of operations, enabling key personnel to advise policy makers accordingly. Many senior politicians, with the appropriate security clearances, had privy to the detail of the material obtained, as all too often this guided their decision making for national and international policy. Despite calls for the SR-71s to be reactivated for Operation Desert Shield in 1990, the requests were denied. However, the continued instability in the Middle East, combined with ethnic violence in the Balkans provided the nucleus for the pro-SR-71 lobby to become increasingly vocal. During the spring of 1994, a deterioration of relations between the US and North Korea was, to many, the final straw. The SR-71 was needed to monitor the situation in these regions, with many Senators and Congressmen joining the call for the programme to be reinstated.

SR-71 61-7967 final flight. Photo by Bob Archer

SR-71 61-7967 final flight. Photo by Bob ArcherThe continued SR-71 operation by NASA was well placed, as the US Congress appropriated $100 million in the fiscal year 1995 defence budget to reactivate both SR-71As and the sole SR-71B for service with the US Air Force. A programme office was established at Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio to oversee the reactivation, with the aircraft being assigned to a Detachment of the 9th Reconnaissance Wing. Despite the headquarters being located at Beale AFB under Air Combat Command, the SR-71 operation was to remain at Edwards AFB, with Detachment 2 being formed. On 15 April 1996, John White, the Deputy Defense Secretary, directed the Air Force to ground the SR-71 due to conflicting language in section 304 of the National Security Act of 1947. However, this was just one of many hurdles which the SR-71 cruised over, on its rocky path back to operational status.

Lockheed Martin was contracted to prepare the two aircraft for operational duty. At the same time the two overseas operating locations at Kadena AB and RAF Mildenhall, began to prepare for possible deployments by the SR-71 on an occasional basis. The situation in the Balkans, embroiled in civil war, was one of the most likely areas of interest, as were certain hostile Middle Eastern nations. Both of these "hot spots" could be covered from RAF Mildenhall. On 1 January 1997, Detachment 2 at Edwards AFB was declared mission ready. The two aircraft, serial 61-7967 and 17971, had adopted the dark red tail band of the 9th RW containing the familiar four Maltese crosses, and the tail code "BB." It seems logical to assume that the Air Force would not devote so much funding to the programme, just to have the aircraft flying training sorties over the high desert area around Edwards AFB. Therefore the return of SR-71 operations to Mildenhall seemed a distinct possibility.

But the SR-71 retained only a few friends at senior level within the Air Force, and even the USAF Chief of Staff, General Ronald Fogleman, was against reactivation of the programme from the start. Therefore, despite backing by politicians, the negative stance by the primary operator was always going to a massive hurdle. In fact, it was an obstacle which even the fastest operational aircraft in history could not overcome. Less than a year after being declared operational, the funding for operations in fiscal year 1998 was withdrawn. On 15 October 1997 President Clinton imposed a "Line Item Veto" on SR-71 funding, which effectively removed the programme. Fifteen days later Headquarters US Air Force directed the termination of all SR-71 operations, and ordered the swift disposal of the fleet. The Veto prevented any further opportunity by politicians to rekindle SR-71 operations at a future date. The revitalised SR-71 programme did not perform any overseas deployments, and the preparations at Mildenhall for a possible return, were quietly abandoned.

SR-71 61-7972. Mildenhall. Photo by Bob Archer

SR-71 61-7972. Mildenhall. Photo by Bob ArcherThe final move by an SR-71 to the U.K. was not by air, exceeding Mach 3 and shooting the characteristic diamond shockwaves into the sky. This journey was completed at a far more sedate pace, with 61-7962 being dismantled and taken by road from Palmdale to board a ship bound for England. The final part of the journey was again by road, to the Imperial War Museum at Duxford to become one of the star exhibits at the new American Air Museum section. The SR-71 arrived on 11 April 2001, and following reassembly, was formerly handed over by General Joseph Ralston, the Supreme Allied Commander Europe at a ceremony held on 14 June. The SR-71 may no longer grace the skies of eastern England, but one is available for generations to enjoy. Somehow, the static exhibit lacks the life and intensity associated with daily operations. The stillness shields the dangers which the aircraft, and its crews faced every time they flew operationally close to the borders of hostile nations. SR-71 missions were hazardous, as more than a 1,000 surface to air missiles were launched, mostly by North Vietnamese air defence sites. No doubt, some were fired at '962. None reached their targets - a testimony to an unsurpassed aircraft. ‘962 was resident at Mildenhall for three periods of duty.

Operations at Mildenhall took place over a sixteen year period. Eleven of these years were regular operations, while the remainder were ad hoc missions. Limited documentation has been released concerning SR-71 operations in Europe. However there were more than 1,000 missions flown, most of which were operational.

The Senior Crown programme performed no overseas operational sorties since being withdrawn late in 1989, and 25 years later, military and political figures still talk of the contribution the aircraft could have made whenever the US is embroiled in combat. During the Kosovo campaign and the second Gulf War, there were calls for the reinstatement of SR-71 operations, due to lack of timely reconnaissance. However, the final death knell for the SR-71 was the advent of the small, highly capable unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), which were cheap to operate, and could loiter for longer periods to obtain data. While not providing exactly the same quantity of intelligence, they were equally as flexible, and were considered "disposable" due to the lack of an onboard crew. No SR-71 advocate could argue against such features.

SR-71 61-7974. Photo by Bob Archer

SR-71 61-7974. Photo by Bob ArcherThe emblem of Detachment 4 was a large SR-71 superimposed over a dart board, reinforcing the anglophile link between the two nations. The emblem was never displayed on the tail of an aircraft while at Mildenhall, instead being exhibited only upon the notice board sign outside their hangar, and within the small office complex. No SR-71 exhibited the emblem on the tail as the aircraft was only with the Det on a temporary duty basis, and remained the property of the parent Wing throughout their overseas deployment. [Note, this was not the case with Detachment 1 at Kadena, whose aircraft frequently carried a large red 1 encircled by a red "Habu" snake. However 61-7980 had the emblem applied to the tail in February 1990 for the delivery flight from Palmdale to nearby Edwards AFB for service with NASA. The emblem was soon removed, as NASA applied their logo to the tail.

Within the Detachment offices were several murals devoted to the SR-71 and support units. Amongst these was a hand drawn celebration of the 25th anniversary of the Blackbird. The Habu Anniversary poem was loosely based upon an advertisement for Pepsi Cola, which was popular at the time :

Kelly inspirin'; Rich thinkin'; Skunk workin';

Recon seein'; Two seatin'; Intelligence gatherin';

J58 drivin'; J.P. 7 burnin'; Missile avoidin';

MiG loosin'; High flyin'; Record settin';

Mach bustin' .................................. BLACKBIRD

The wording included as many important aspects relevant to the SR-71. The quarter century anniversary was from 22 December 1964 to 22 December 1989.

Despite the intervening quarter of a century since the "Blackbird" ceased operations in Europe, the type is remembered with much fondness by those who had the opportunity to experience an SR-71 departure. Legendary designers Kelly Johnson, and his loyal assistant Ben Rich have both passed away, taking with them their "slide-rule" technology, which produced the SR-71 and later the F-117A. It is unlikely such technological masterpieces will be produced with creative genius, as computers have largely replaced the simplistic "man in the loop." They and their products may be consigned to history, but their contribution to the defence of the United States and their NATO allies is almost immeasurable.

SR-71 Visits to the UK - In order of Arrival

61-7972 9 September 1974 - 13 September 1974

61-7972 20 April 1976 - 30 April 1976

61-7962 6 September 1976 - 18 September 1976

61-7958 7 January 1977 - 17 January 1977

61-7958 16 May 1977 - 31 May 1977

61-7976 24 October 1977 - 16 November 1977

61-7964 24 April 1978 - 12 May 1978

61-7964 16 October 1978 - 2 November 1978

61-7972 12 March 1979 - 28 March 1979

61-7979 17 April 1979 - 2 May 1979

61-7976 18 October 1979 - 13 November 1979

61-7976 9 April 1980 - 9 May 1980

61-7972 13 September 1980 - 2 November 1980

61-7964 12 December 1980 - 7 March 1981

61-7972 6 March 1981 - 5 May 1981

61-7964 16 August 1981 - 6 November 1981 (arr from Bodo - diverted on flight from Beale on 13 Aug)

61-7958 16 December 1981 - 21 December 1981

61-7980 5 January 1982 - 27 April 1982

61-7974 30 April 1982 - 13 December 1982 (at Bodo 7 May to 9 May)

61-7972 18 December 1982 - 6 July 1983

61-7971 23 December 1982 - 2 February 1983

61-7980 7 March 1983 - 6 September 1983

61-7962 9 July 1983 - 30 July 1983 (in reality 61-7955 re-serialed !!)

61-7974 2 August 1983 - (??) July 1984

61-7958 9 September 1983 - 12 June 1984

61-7979 14 June 1984 - (??) July 1985 (mid month)

61-7975 (??) July 1984 - 16 October 1984

61-7962 19 October 1984 - (??) October 1985 (mid month)

61-7980 19 July 1985 - 29 October 1986

61-7960 29 October 1985 - 29 January 1987

61-7973 1 November 1986 - 22 July 1987 (for repairs)

61-7964 5 February 1987 - (??) March 1988 (mid month)

61-7980 27 July 1987 - 3 October 1988 (from RAF Lakenheath)

61-7971 13 March 1988 - 28 February 1989

61-7964 5 October 1988 (to RAF Lakenheath) - 18 January 1990

61-7967 2 March 1989 - 19 January 1990

Bob Archer

March 2015

Разделы сайта

Разделы сайта