Interview conducted by O. Korytov and K.Chirkin

Literary presentation by I. Zhidov

Comments by I. Seidov, I. Zhidov, I. Grinberg and S. Vakhrushev

Translation and editing by Oleg Korytov and James Gebhardt

Baskov, Anatolii Vasilievich – former weapons master from 224th IAP.

Left to right: V.Buchelnikov, -, S.Mospanov, -, A.Baskov

Left to right: V.Buchelnikov, -, S.Mospanov, -, A.BaskovBaskov, Anatolii: I was born June 9, 1931, in the village Annenskaya, Kaduyskii region of Vologodskaya District. My parents were average peasants. We used to have a horse, a sleigh, and all the things that were needed for peasant’s life, so to say. Dad used to go to Leningrad as a seasonal worker. In the spring, we altogether had sowed the crops, and then he left until autumn. After reaping the crops, he left us again for winter. Sometimes he stayed with us for summer or winter. I attended 1st Grade in the school in the village Pryagaevo, which was about three kilometers away.

In the winter of 1939, right before war with Finland, Dad brought us to Ropsha, which is near Leningrad. I still remember how we traveled by tram No. 36 to Strelna, and then we had to travel by sleigh to Ropsha garrison. Dad was a good specialist, and he was assigned as the chief of a builders’ team. We lived in the right wing of Ropsha Palace, and stayed there until August 1941. Dad was a builder at the local airfield. Three houses that he built are still in use in Ropsha.

- How did you find out about war?

In the same manner as everyone else. In the morning we were informed over the radio that our cities had been bombed. We were in shock.

- When did you start to think that it was time to leave Ropsha?

When Ropsha was bombed and first casualties appeared, we understood that it was no longer safe there. I remember how our airplanes fought dogfights with Germans over Ropsha. I saw how six of our pilots were buried there, and I still remember the surname of one of them – Bogolyubov. (Bogolyubov, Ivan Andreevich, captain, squadron commander from 44 IAP. His MiG-3 was shot down in a dogfight over Volosovo; he bailed out, and was strafed and killed by enemy fighters while descending with parachute. Died 22.07.194, buried in Ropsha).

Once, after a loud bang, we, still boys, saw that just 30 meters away from our palace a Soviet fighter had crashed through the tree tops into the ground. The pilot was dead.

When pilots were killed, a commissar would go to their wives and say:

“Be brave…”

The coffin with the dead pilot’s remains was covered by red fabric and transported by truck to the local cemetery. Usually they were buried near the church that was just off the Ropsha airfield.

Before the war, there was a “House of the RKKA” in that church, something like a club, and in the evenings were movies shown there, which we liked to attend. Nearby was a house – so called “Uncle Pasha’s home” – he was a chief of this club. My father was in good friendship with him. Uncle Pasha had a family: wife and four kids – Boris, German, Vladimir and a girl, whose name I do not remember. We played together quite often.

Germans began flying in the vicinity of Ropsha airfield; they flew and dropped bombs right over the park. Once, a bomb hit their home; shrapnel killed German and Uncle Pashas wife, and their girl was wounded in the right thigh and some flesh was ripped out of her abdomen and crotch… She bled severely.

I remember how a German airplane strafed a truck on the road. It was used to bring food to the airfield. There were three victims: the truck driver, a chef and a quite fat man, and a female chef, Tatar by nationality. After that incident, mom said to us:

“Do not run away; if we will have to die, let us die altogether.”

Nearby was a Krasnoye Selo-Strelna road, and we all the time saw truck convoys loaded with soldiers and sailors moving toward the front line. There were a lot of them, they moved day and night – and almost none came back. It seems that most of them perished, and we were very sorry for them.

- Were you expecting evacuation?

No. We had to stay in the basement for almost a week, when on 26 August, a military truck came to our home, and we were told:

“Get loaded fast, you will be evacuated.”

We left Ropsha without our father; that day he had been sent to Gorelovo airfield, so he had no idea what had happened.

We were loaded without any belongings, and brought to the square in front of Moskovskii railway station. It was crammed with refugees. All we had for food was a small bag of dried bread.

- Were you and other refugees fed there?

No, nobody was thinking about feeding us. I remember that a man came to us and tried to steal our bread crumbs from us. Mom was very upset, but that man said:

“You have at least this, while we have nothing. We barely escaped and have no food, we are starving.”

We had to spend several days at the railway station. A lot of refugees were sent out before us. I remember one train of 60 cars with full Red Cross markings; it was loaded with children, women and elderly people and sent to Vologda. It was hit by German airplanes near Mga, and when we were passing through that station later, we saw the wreckage and what remained of those people.

We waited for Dad at the railway station, and we got lucky – mom saw him behind the fence, and by her demand he was allowed to come to us.

Soon we were loaded onto the train and sent to the east. Dad stayed in Leningrad, and perished along with my older brother, who turned 17 in 1941. We were lucky, as we went through Mga at night, but still, we were bombed. A German bomber dropped two bombs, but missed. I was sleeping at the time, and felt like a light punch through sleep. Only in the morning was I told that we had been bombed.

We had to travel 4.5 days to cover 450 km. We went to Kaduy, that’s 40 km from Cherepovets.

- It’s 1941, the army is retreating, a lot of refugees… How did people react to all of this?

I was a 10-year-old boy, and can’t say anything substantial about that. But it was needed to “defend the Motherland.”

Before the war, we kids ran through garrison, spoke to the soldiers and officers, and I heard from them:

“If we solved the question with the Finns, we will deal with Germans, too”.

And then – we retreated! Of course, it was a shock! Before the war, we were told that our airplanes and pilots were best in the world, and then we saw them fall out of the skies.

- Let’s return to your evacuation. You were brought to Cherepovets, and?

We actually returned to our homeland, where stood our empty house, and there we had about three square km of ground and a barn. We lived there along with Starshina Zalesov's family. Dad knew them well; we were evacuated in the same train, and let them live with us. Zalesov’s wife and their two daughters lived with us for almost a year. After them we gave shelter to Finn Amalia and her son Arno, but then her husband came after her too. We kept in touch by mail long after the war.

We lived in hunger. Some bread was issued for food stamps, but it was insufficient. In the spring I had to go to the potato field with my two sisters and seek leftover potatoes from autumn. We dug them out and brought them home. Mom threw out what was absolutely rotten and inedible, and baked some pancakes with crude oil. We had no butter or salt. Then, the time came when we had to eat dry clover flowers, it was called puzhina. In the spring we had to eat wild grass… We barely made it through!

Mom was pregnant when she came to the village, and gave birth to a boy whom she named Leonid, but she had no milk. We tried to give him wet bread in some clean clothes… Horrible! His rectum had fallen off, and we had only some crushed dry peas to sprinkle over it to make it back in. That was all the medicine available to us! So, one day I came home from school, and saw him lying dead on the table. It was so horrible!

- Did the kolkhoz help you?

At first I don’t remember any help at all, but after mom went to work at the kolkhoz as a horseman, it got better. In the summer 1942, we were given some grain. We ate fresh bread, and for some time we were like drunk – we did not know that it was risky to eat a lot after a starvation period. (It seems that Kolkhos issued some rye to the family, and children ate freshly-baked bread. Technology for producing rye bread states that it has to stay idle for at least 12 hours – cases of similar origin were known to cause “alcohol intoxication” even in strong young men.)

Then the kolkhoz provided us with a piglet and a calf, and then we got some sheep.

There were only old men, women and children in the village, so at 13 years I already had to work full time at the field, the same as everybody else.

- Were there tractors in the village?

Yes, we had had them since the 1930s; there were different methods of mechanization.

- Was there a school in the village?

I had to go to Vakhonkovskaya elementary school, which was 700 meters across the river. There was no normal paper. We were given large pieces of brown paper used to wrap stuff, so we had to cut it to the needed size and make notebooks to write in.

When the Germans captured Tikhvin in 1942, some people from there were sent to us. They came in to dig trenches, and left when Tikhvin was liberated.

They all had hand-made footwear. Several of them were sent to live in our house. They spoke a language that we couldn’t understand. I remember when they divided bread, one turned around and somebody asked, showing some portion:

“Kimyn? (To whom?).”

I remember that word. Very quickly I learned that these were Kalmyks, who spoke a Turkish dialect. [Kalmykia is located along the west bank of the Volga River where it enters the Caspian Sea. It has a majority Bhuddist population. Ed.]

These people mobilized from Povolzhye [region along the Volga] brought lice with them. That was a true nightmare! Our only salvation was the sauna – we washed in hot water. I also remember that before I went to school, I ironed my shirt. Mom made a fire in the stove and heated the iron. I used it, and when the hot iron went across the shirt I could hear lice popping under the heat. Mom made our pants and shirts herself.

- How did you receive information about the situation at the fronts?

There was no radio in our village, so all the information came from the village Nikolskoye, which was one kilometer away. There was a shop there; perhaps, they had a radio, too.

- How long did you live in the village?

We lived there until 1946. My cousin lived in Leningrad, and she suggested that we study in a technical education school. In 1946, my cousin Leonid and I went to study in Leningrad. We lived for a couple of weeks at female hostel near Apraksin Dvor, where my cousin used to live, and then we were accepted to 3rd Industrial Trade School at Kondratyevskii Prospect.

Starting from 1 September, we began studying in the school and were given a place to live in the hostel at Meshlovskii Crossroads. We lived there for eight month, and travelled by tram to study. Tram service was reopened on a regular basis in 1944. Leningrad was severely damaged, and there were a lot of destroyed buildings in 1946, I saw that myself.

Then we were moved to 1st Murinskii prospect, where we lived until the end of school.

- Did you how German war criminals were hanged in Leningrad?

Yes, I do remember; we were there when some criminals were hanged near Gigant. There was no announcement, it was just the fact that our school was nearby, and a rumor went through, so we all ran there to take a look. There was a huge crowd. The Germans were brought in by trucks escorted by soldiers, and then they were hung. People at the square were overwhelmed with hatred – it was in the air. No one applauded when the execution took place, but there were some encouraging shouts.

(8 war criminals were hanged in Leningrad, mostly for murdering civilian population. Videos and list of criminals is available over internet).

- There is an opinion that pupils of professional schools were a bunch of young criminals. What is your opinion?

No, we had outstanding order and discipline. We had uniforms, every pupil got a set. In the beginning, in 1946, food was poor, we called it khryapa – overcooked, overboiled large chunks of cabbage; but we were so hungry, that even this absolutely awful taste was good enough to ask for more. We had a portion of 400 grams of bread per day, and still some managed to sell it to get money for Eskimo ice-cream. We were fed three times a day. Text books were free, as was the tram.

- Were you baptized?

Yes.

-What was the opinion back then?

Then it was rather normal. My grandfather Petr Rozov was a very religious and honest man. He was enlisted in the army at the age of 40 and had to fight in WWI. I still have a postcard that he sent from the front to the village, saying: “I am sending you some money to buy land and poles. Thank you for package.” A soldier of the Tsar’s army sent money home, while he received some goods and food from home.

The village that he lived in was called Pelemen, and he had a good farm; besides, he was also a local tailor. A family of drunkards lived nearby, and their man had accused my grandfather of some crime. He was arrested. When Grandmother went to the police to find out what had happened and where my grandfather was held, some officer told her:

“Do not come here and do not inquire, or you may end up at the same place as he.”

Other officers lied that he was in prison, but actually by that time he had been shot, either in the NKVD building in Leningrad, or in Levashovo. I go to Levashovo burial ground annually to mourn my grandfather. I took his photo there. There is no way to find out where exactly his grave is – a lot of people buried there – Finns, Russians, Poles. Some were executed in family groups. Nowadays, there is a memorial there.

- How long did you study in the school?

For two years. Upon graduating, I received 4th rank, and was sent to Bolshaya Okhta to “Lenenergo” plant, which still exists.

- When did you start actual work in practice?

We worked right from the start. There was a lathe workshop nearby, and there were different lathes, even an automatic one, built in America. I also remember that when I worked at “Lenenergo,” there were two American automatic machines with an inscription “From Roosevelt to Stalin.”

I worked there for about eight months, when some Komsomol agitator came to us and suggested we go to work at a military plant. I earned 700 rubles then, and it was pretty decent money. We lived in the hostel provided by plant, ate at the plant’s canteen, we even could eat for credit. This komsomol worker said to us that we will be working at new turning lathe, earning even more money. I and several other men decided to go there.

This new plant produced artillery rounds and other military supplies; everywhere you could see armed guards. We were not allowed to work by our specialties, but instead we were sent to fix glassing, the roof and so on. This work was paid at a lower wage – about 300 rubles, so I was really not interested in working there anymore. For three months I worked there rebuilding one of the shops. Everything was in rubble after the war, and it was necessary to repair what lay in ruins. We understood that, but we also had to live, we wanted to eat regularly. We went to different seniors, and asked why we had been lied to. They always replied:

“Shut your mouth and do what you have been told.”

So, we left without an answer. All the time I thought how to get out of the plant. There was a law then, forbidding free change of working place.

Suddenly, when I was in the clinic for some check up, I told my story to one doctor, and she took pity on me. She wrote a medical document that I was in need of serious treatment for some pulmonary disease. This paper gave me the possibility to leave the military plant.

I began working at “Nevgvozd’” plant, and worked there for about seven months; they even sent me to the “recreation house” for treatment of my lungs.

At this new place I once again earned 700 rubles, and could eat at the canteen three times a day for four rubles.

But, for some reason, I decided that my salary was not enough and, out of sheer stupidity, was absent for a week. Then a notice from court was sent to my hostel. My brigadier [team leader] was there already, and a question was asked to us, why the worker was absent for whole week without official leave or sick list? Then laws about absence at work were still as at war time – five minutes late – 25 percent of salary will be withheld; for a long absence you could get up to three months in jail, even more. That was due to wartime law!

The judge said that if I would return to work straight away, he would not punish me, and asked if I was satisfied with this decision.

I, once again, decided to be a wise guy:

“I’d rather go to jail than return to that plant!”

So I was sentenced to three months in jail. One week I spent in the Leningrad city prison “Kresty (Crosses)” – we were sitting four inmates in one cell. I was in cell No 731.

In one week I was sent to Gavan to a labor camp, where there were over 500 men already. All kinds – [men sentenced to] three months and 15 years together. We lived in a large building, which was divided into rooms, and each one had several inmates sleeping in two-storey beds.

- What did you do in this camp?

We built a research facility nearby. We were escorted into the working zone, where we worked along with free people. We tried to order vodka through them. But when we returned, we were carefully searched, and if alcohol was found, the bottles were smashed in front of us all.

Since I had a short term, I had a place at the top bunk, while below me was a man sentenced for murder, and for some reason he liked me. He warned all the other criminals not to touch me. We became friends, and even shared food that his wife and my sister brought to us. I even gained weight there. On the floor below us was a section for youngsters that were guarded by so called “self guards” – senior prisoners, tasked with upholding discipline among them. So, these “kiddies” murdered one of the “self guards.”

I was sentenced in April 1950, and I served my time in three months. I left the prison, crossed my heart, and as superstition ordered, left without looking back. After leaving the camp, I found work at the woodworks, where I had worked for nine months with a salary of 900 rubles.

I was already 19 years old and, in April 1951, I got a notice from draft board, and I was conscripted.

- Why you were called up so late?

Can’t say, really. Perhaps, I was supposed to be called in during the previous draft, when I was doing time.

- Had your sentence any effect on your enlistment?

Not at all. I had a paragraph for casual things, not thievery or something.

I was sent to ShMAS (Shkola mladshikh aviatsionnykh spetsialistov - School for junior aviation specialists). We travelled by train for over 7000 kilometers to Spassk-Dalniy for over a month. We arrived there in May, when it as already warm. Near Spassk-Dalniy was an airfield, packed with old airplanes – piston-engined fighters – La’s, Shturmoviks [Il-2’s] and so on. For three months we underwent a course of the young soldier, and then we began actual studying. I was sent to study as a weapons mechanic, and learned how to use primers, guns, cannons, and bombs. Loading airplanes with bombs was also my responsibility.

At the beginning we were fed by that same khryapa, and we started objecting to such menu. Things were cleared by an eight-kilometer cross-country high speed march with full load – rifle, rucsack, gas mask and other stuff. Then we were formed up at the square and we had to stand there for a long time. But soon the menu improved.

After graduating from ShMAS, I was sent to railway station Babstovo, in the Jewish Autonomous District. I was the only one from our ShMAS there. I came to the regiment equipped with P-63 KingCobras, produced by Americans, which they had sent to us by lend-lease.

I can’t recall the unit number, but I still remember some of the commanding officers: the regiment commander was Lt. Colonel Savchenko, the chief of staff was Major Matytcin, the 1st squadron commander, in which I served, was Captain Chernyshov.

It was very difficult job to service airplanes at winter time. The airfield was located in the valley, temperature was below - 30 degrees centigrade, so we had to use special heating lamps to warm up the planes. There were no shelters, so the airplanes simply stood at the parking area. We were issued warm coats with high fur collar, warm hats and gloves.

The P-63 had a nose gear, so it was used intensively for training pilots for the MiG-15, which also had a nose gear.

The KingCobra had an M-4 37 mm cannon that fired through the propeller.

Quite commonly pilots flew firing practice missions. We had to ensure correct work of the “sausage” (drogue used for aerial gunnery training). We had to extend it by lines on both sides of the runway, and when the airplane began its take off, we ran after it until this “sausage” was filled with air, and then we would release the lines. The towing airplane was piloted by the most experienced pilot, while others had to shoot at the cone from different angles, in order not to hit the towing plane.

After gunnery practice, the pilot of the towing airplane would drop the “sausage” and we would run to count holes. Before loading, bullets were painted differently for each pilot, so that we could tell which pilot made which hole.

What else did we do? We had to take away parachutes after flights were over, or we had to go on guard duty. We had to go to the airplane parking area with rifles.

- What were the relations between privates and officers?

Hazing was nonexistent. [Hazing, bullying – dedovshchina (“grandfathering”) in Russian, has been the scourge of the Soviet/Russian military forces almost in perpetuity. It at times is so brutal that soldiers are beaten to death or commit suicide. The practice is based on seniority, driven by older draft cohorts preying upon younger draft cohorts. Being first introduced during Tsar time (when soldiers service was a life-time experience), it had an intention of introducing younger soldiers to regiments tradition and solving disputes without calling officers. This intention was absolutely lost after Khruschov’s reforms, when former criminals were allowed to also be drafted into the army and brought prison hierarchy with them.] Mostly, soldiers served for 5, 6, 8 years. Because boys of their drafting age were lost in the GPW. These soldiers were of the 1921–24 cohort, and that is why they had to serve long, but they were paid well for their long service. They were demobilized in 1952, and I became a weapons mechanic.

Once, I got a torn boot, and I decided to ask squadron commander Chernyshov to issue me a new pair. But he replied:

“Do you know that we had to fly combat missions in self-made shoes?”

He took part in the GPW. After that incident, I was sent to war. I do not know why, but another electrical mechanic and I were sent to Korea.

- Do you know of any cases when American airplanes attacked our airfields before Korean War?

No, there were no such cases before the war in Korea. We knew that their planes commonly flew near our borders, but they never strafed our airfields.

(On October 8, 1950, American fighters attacked Sukhaya Rechka airfield, but the Korean War had already begun.)

- Were you told that you were going to war?

When we arrived at the regiment headquarters, Major Matytsin told us that we would go to the district headquarters in Chita, and there we would receive further instructions. For farewells, he said to us:

“Do not stain our regiment’s honor!”

And that was it.

- Did you travel with an officer?

We were traveling together with that mechanic without any escorts. At the headquarters in Chita, we were sent to an airfield service battalion. Of course, we were unsatisfied with this transfer – we had studied to work with airplanes. Once again, in a week’s time, we went to the district headquarters, where we got new direction to an airfield near Chita. At that place was a bomber regiment equipped with Tu-2 bombers. When we arrived there, we were sent to 1st squadron, under the command of Major Kyun, a German by nationality. I believe he was a Hero of the Soviet Union (HSU). I remember that in the Red room I saw portraits of 11 HSUs that were in the regiment.

We arrived in an ordinary soldier’s uniform, so here we immediately were given technical gear. We were introduced to our crew, and studied Tu-2 weapons. After just a week in this regiment, we were called to the front at the formation, and Major Kyun read us an order – to go to an assembly point in Chita.

There were about 30–40 men at the assembly point. In the evening of that day, we were loaded onto the train and went south, to the Pogranichnaya railway station at the Chinese border.

There we lived in the barracks near the station for almost a week. There was no information given to us, but each day we received a new hypo shot – against plague, cholera, smallpox, encephalitis and so on.

- Were there any rumors circulating?

Everything was kept in secret, and no rumors were circulating.

In a week’s time, we were loaded to the train again, crossed the Chinese border, and travelled along the KVZhD (Kitaysko-Vostochnaya zheleznaya doroga – Chinese-Eastern Railway), crossed the Great Khingan range with its steep climbs and descents.

Along the way, we were fed in the restaurant car. At the stations we were visited by Russians who lived there before revolution and those who had escaped to China after the revolution. They told us that they were willing to return to the motherland, and that they were waiting for Soviet passports.

Before we departed for China, we had to remove all recognition elements from our uniforms, and that’s the way we arrived in Harbin. When we de-trained at the railway station, we were met by the commander of forces of the Peoples Liberation Army of China, Peng Dehuai. We surrounded him in a tight circle. He spoke decent Russian, and we talked for about 20 minutes. He told us that he had studied in the Academy in Moscow. We asked him questions, and he finally told us why we had been sent there:

“Comrades, you will serve here, defending China and the Soviet Union here.”

He explained that American airplanes flew as far as Mukden, which is 450 km from Korean border. Thus, he revealed the truth of what we were going to do.

In the evening, we were loaded onto the train again and were sent to the south. We were brought to Mukden, where we were sent to the sauna, and there we received Chinese militia uniforms. It was grayish in color, with no shoulder boards, just a Chinese inscription on the left side of the chest, plain trousers of the same color and shoes. And a hat with a star. No way to establish the rank.

- When did you arrive in China?

I arrived at Mukden. in the beginning of 1952. After we were dressed, we were fed and then we went to the airfield near Mukden. There we saw MiG-15 jet fighters.

- What was your regiment number?

Military unit 40332, and the regiment itself was the 224th IAP. Before that I had seen only piston-engine airplanes. We studied how to service MiGs for a week we studied. As a weapons mechanic, I studied the cannon mount – it was equipped with the NS-37 37mm cannon and two NR-23 23mm cannons. The cannon mount was very well thought designed – it could be raised and lowered, and was fastened in place when ready. (MiG15bis had 40 37mm cannon rounds for NS-37D cannons and 80 23mm cannon rounds for each NS-23KM cannon. When American specialists found out that so few rounds were on board of MiG, they were shocked)

- The Western press has pointed out the following deficiencies of MiG-15 armament: low fire rate, insufficient ammo quantity, and weapons mount that was not rigidly fastened to the airplane, which in turn led to wide shell spread. What can you say about this?

First of all, the weapons mount was rigidly fixed in the airplane. It could be lowered using cables, but then it was secured once again. As for the rest, I didn’t even think of them, and pilots never complained about anything that you said. (MiG-15s cannons had very good characteristics for those days. NS-37D would fire it’s ammo in 9,6 seconds, while NR-23 KM in 5,6)

- Did you disassemble the cannons on the MiG-15, or just clean them?

We just cleaned them after use, and that was it.

- Who loaded the ammo belts?

We very rarely did; they were brought to us already loaded. Ammo boxes came with belts, so we just unloaded the used ammo belt and loaded the new one. When airplane returned from a mission, we had to check to see if a round was in the barrel; if it was there, we had to remove it.

I was assigned to the crew of Captain Siskov, airplane No 757. The airplane’s technician was Lieutenant Shmaglienko and I was weapons mechanic, Viktor Guselnikov – engine mechanic.

Our 1st squadron commander was Major Svishev.

(It was MiG-15bis serial number 2715357 built in Novosibirsk air plant, that previousely fought with 148th GvIAP. All his victories last Soviet ace of Korean War B. Siskov achieved flying this airplane)

Siskov, Ermakov, German

Siskov, Ermakov, German

Independent of our specialty, we had to do everything: refuel, hang drop tanks, help with servicing.

- Were there cases when missions were cancelled due to poor servicing?

I remember only one such case, when a technician forgot to remove the cover from the pitot tube, even though it was red in color. The pilot took off, but returned immediately after takeoff and safely landed.

After missions were flown, technical crews had a debriefing. It was made by regiment engineer Viktor Zhizanov. Once he showed us a large caliber round from Sabre and said:

“Look at the presents that fly above our heads – be careful, guys.”

When there was a fight above the airfield, shells were flying not only upward, but downward as well, regardless of who fired them; besides, there were AAA shell fragments falling down, so it was quite easy to get wounds from all this stuff falling down.

In Dapu we had a twin NR-23 turret to fend off Sabres, which was commandeered by Senior Sergeant Podkolsin. It was a factory-produced turret. Sergeant Podkolsin helped to protect our airplanes while they were taking off and landing. Since he could mistake our airplane and an enemy’s, he could only fire after permission from the command post, and then only if they were sure that it was the enemy.

After the Korean War was over, Podkolsin got a “for military achievements” medal, even though he didn’t actually shoot anything down.

We transferred to Dapu in January 1953, and three months later the regiment moved to Andun. Our airplanes flew there, while ground crews moved by trucks.

In Mukden our pilots Berelidze and Siskov already had scored two American airplanes; they added 1–2 more in Dapu, and the rest they got in Andun.

By the way, in the books about the Korean War, it is stated that Berelidze and Siskov had five downed and one damaged airplanes each, but I remember very well that our airplane wore seven stars – six shot down and one damaged. I do not know how many stars Grigorii Berelidze had, since he was in the 3rd squadron.

- Where were the victory stars on the Siskov’s airplane?

On the left… or right? I can’t recall, but on one side only. “Shot down” was s full red star; “damaged” was just a red outline of the star.

(According to all known photos of the KW period stars were painted on the left)

- The aircraft that you received in 224th regiment – were they new or used in combat?

I can’t say. But we had no problems with the aircraft.

- How they were painted?

All airplanes were camouflaged. The underside was blue, the upper side was spots and stripes of different colors: gray, green, and brown. (After it’s arrival to Korea 224th IAP received airplanes from previously fighting regiments with one tone gray or green-silver paint and a few new airplanes in typical silver finish. At least four times airplanes were repainted to different camouflage types)

- Were there airplanes with red noses in your regiment?

No, there was no such practice. Identification markings were Korean stars on the fuselage closer to the fin. And there were markings on the wings.

I read a story of Siskov’s former wingman, Klimov, who with time he rose to the rank of lieutenant general of aviation.

Perhaps, in order to protect “the honor of his “regimental dress uniform.” Klimov stated that Siskov was never hit during that war, but Siskov once brought 96 holes back to Andun. I’m an eye witness – I personally counted those holes. The whole rear section of the airplane was riddled with bullets from a Sabre—stabilizers, rudders, fin and both wings.

Even though we had special technical service, we fixed the airplane by ourselves at the airfield. Our chief was Lieutenant of Technical Service Shmaglienko. Siskov came back damaged and made a belly landing near the runway, right in front of our parking area. We raised the airplane with jacks, fixed the damaged hydraulics and lowered the landing gear. A container with new wings and other parts was brought to us. We disassembled the fuselage and checked the engine. I remember that one blade of either the compressor or turbine was damaged by a bullet – it tore off the upper quarter of the blade and made a hole in the right side of the fuselage. I believe that we did not change the engine. The front side of the airplane did not suffer, but all the rear part, up to the cockpit, was changed, along with both wings and stabilizer and fin. Then we had to apply camouflage to the new parts.

I remember well that Siskov’s airplane was damaged due to an unpleasant event that took place. Spares came from the USSR with Soviet markings, so Viktor Buchelnikov and I had to wash them out with acetone. Buchelnikov was splashing acetone down the side of the fuselage, and the spray hit me in the face and eyes. I thought that my eyes would burst. I yelled, and someone brought a bucket of water. I dove into the water and washed my eyes. Then someone brought some wine, and we washed my eyes with it. This is something I will never forget.

The airplane’s number remained 757, and Siskov kept flying it. Siskov flew another airplane temporarily, for a week or two, while we were fixing the damage.

Before missions, we had to hang drop tanks. When enemy aircraft met each other in the air, they dropped them. We had drop-shaped tanks of Chinese production of quite poor quality. They made it of zinc-plated iron. The Americans had duraluminum tanks with fins. When two large formations met in the air, hundreds of tanks fell out of the sky. Ours smashed into pancakes, while the American tanks even made a safe landing, sometimes in decent condition. The Chinese took American tanks, cut out the upper part, and they had a single seat boat.

In the summer, at the end of June or beginning of July 1953, there were heavy rains, and a dam near Andun was breached. Our airfield was covered with water over a meter deep. The surrounding area was also flooded, including rice paddies. This lasted for over a week.

We were informed in advance, and had time to move our airplanes to higher ground, where they did not suffer from water. All that week we had to use boats to get to the depots, which were made from airplane containers.

What else – I remember how Viktor Buchelnikov and I were walking, when we heard “chvik-chvik” – bullets flying over us. Somebody had fired at us from nearby hills. At the Dapu airfield were Nationalist Chinese POWs guarded by soldiers, used as unqualified workforce.

Once I was walking past our squadron’s parking area, which was near the hill, and there was a road going at the foot of the hill past our parking. I noticed yellow bricks in the grass – something like soap. I picked one of them up, and saw a hole for the detonator – there was at least a hundred pieces of explosives lying there. Somebody had prepared it for a reason – if it all blew up, almost all the airplanes at our parking area would have been damaged or destroyed.

I ran to the squadron engineer and reported to him. The explosives were removed and I was told to keep silent about it.

- Did you share your airfield with Chinese or North Korean air force?

Yes, that happened. In Andun our regiment was stationed on one side of the runway and Chinese and North Korean regiments were on the opposite side. I remember walking past their parking, and I noticed one airplane with 10 victory stars. I can’t say whether it was a Chinese or Korean airplane.

I walked toward my airplane, and saw a dogfight above the Yalu. I was maybe 300–400 meters away from the river. Three American airplanes were chasing one MiG-15, and soon it was shot down. The pilot ejected right over the river. One American airplane turned around and strafed him. Our parachutes were made of several pieces of cloth, so that if one or two pieces were pierced, it was still good enough to bring pilot to safety. But this time the parachute was ripped to shreds, and the pilot fell into the water. Meanwhile, the other American airplanes kept shooting at the falling MiG. We said among ourselves that the Americans were more interested in raising their scores than in shooting airplanes down. In order to have a confirmation, they had to bring home a video proof that they had fired at something.

On the next day, I heard that it was Chinese pilot, and that he was to be buried that day.

- Is it true that our pilots believed that Chinese and North Korean pilots had poor training?

This was discussed, beginning with the fact that they were poorly fed. I can’t recall if they came to us, but our pilots visited them, and were surprised by their ration – they were fed like ordinary infantry soldiers.

My Chinese friend in Korea -

My Chinese friend in Korea -

Ho Fyn Myn

I didn’t speak the Chinese or Korean language, just some separate words, and that is why contacts were episodic. For example, I once witnessed a strike of American airplanes at the bridge. They came down one by one. Our pilots and AAA gunners were trying to fend them off. I was not the only one to look at them; some Chinese soldiers werenearby. I spoke to one of them, pointing at his PPSh [Shpagin submachine gun, 7.62x25mm]:

“Ho”? (“Good?”)

The Chinese smiled and replied:

“Ho, Ho”! (“Good, good”!)

I also recall that when we guarded a barracks, we had half of a building’s perimeter to cover – the other half was covered by a Chinese guard, and we met at the corners. Sometimes we had to guard it from inside as well.

- How you were fed? Was it local cuisine?

We were fed very well, no complaints about that! We were served by Chinese and the food was also Chinese.

By the way, I recall one food-related incident from Dapu. I saw Chinese that were hitting a live pig hung by its feet. I asked them, why are you that? By that time some Chinese already spoke Russian, and they explained that this way meat would be tender and fluffy.

We had a three-course menu, along with Chinese beer; pilots could get vodka. Technicians and pilots lived separately in Andun, so when I was on guard duty at the pilots’ quarters, I saw piles of boxes with empty vodka bottles. There was some Russian tycoon in China, who produced vodka, beer and wine under Russian names, and that was what we could get. Bottles were not passed for re-use or recycling, and simply accumulated there for years.

Vodka was stinky, but very strong, and there were 2 versions of it - “Zhemchug (pearl)” and “Parovoz (Steam Locomotive)”. (After accomplishing missions pilots received 100 grams of vodka as stress relief method. They were issued vodka “Zhemchug” produced by “Churov and Co” and a bottle of Chinese beer. Beer produced in Tsindao was particularly valued, since plant for it’s production was built by Germans with German recipie. Alternative for wine was Chinese Gaolyan wine)

- Did you receive any money?

I received a portion of my salary there in yuan, and a portion of my salary went to the bank in USSR—the exact proportion I cannot now recall.

As a weapons master I earned 175 rubles per month. The sergeant-mechanic earned 900. We did everything together, but there was such a big difference in salary. I spent my yuan in China – I bought a suit there. It was tailored for me by a local, right before I returned to the USSR. About a month after I came home, I sold it for 1400 rubles.

- You were in need of money?

No, I had enough money. I don’t know why I sold it. I just did!

301st IAP. A.Baskov

301st IAP. A.Baskov

Yes, that’s right. After returning from China, I served for two more years at the Varfolomeevka railway station; there was another airfield nearby – Sysoyevka, and mountain Sikhote-Alyn was three kilometers from our runway. Sysoyvka had a concrete runway, we had a metal one.

- Do you remember when Siskov’s airplane was damaged?

I remember it was at the warm period – summer or spring 1953. I told what I saw, and my words are in contradiction to what former wingman of Siskov – Lieutenant Klimov, who claimed that Siskov was never hit in combat.

My words can be confirmed by airplane technician Shmaglienko, if he is still alive. Then he was a lieutenant, a good fellow; we used to call him “Shmaga,” and he was 2–3 years older than I.

Then we had a weapons mechanic with the surname Kovbasa. He was either a squadron or flight weapons mechanic, but he could interfere with our work. I remember two incidents, when he unintentionally forgot special plates in the cannons that were inserted on the ground to prevent undesired fire. Both times I found them, and got citations for good service. But once, a pilot whose name I have forgotten by now, returned to base in an outrage – he jumped out of the airplane, took out his pistol and was about to open fire at his weapons mechanic. His guns did not fire and it almost got him killed. Everything ended well – other people caught him and took his pistol away. But that’s what sometimes happened!

- Did Siskov tell you what had happened in that dogfight when he was shot up?

Siskov did not talk a lot to his technical crew. We did our business, reported to him that his airplane was ready for action, and he would silently settle in the cockpit and take off.

Grigorii Berelidze was quite the opposite – a very talkative and cheerful man. But at war time it is not so important who talked a lot, but who fought well. Siskov did not talk a lot, but he was a good fighter.

- According to documents, your squadron lost 12 airplanes in Korea skies and three pilots: Nikolay Sokolov, Vladimir Markov and Vil Kulaev. Do you remember what happened to them?

That I can’t recall. It was more common to lose young, inexperienced pilots, not those who had fought in the GPW.

I remember one incident: I was appointed to the position of assistant to the flight controller at the regiment’s control tower. I had a visor, and had to report to the flight controller about incoming airplanes. I could see the tactical number and even the face of the pilot through those visors. It was also my responsibility to warn about Sabre presence, and they were commonly trying to shoot down our airplanes on final approach.

I remember how pilot Captain Ugryumov was about to land at an altitude of about 10 meters. Then suddenly the sound of gunfire. It was impossible to mix Sabre machine guns and our cannons firing. I heard a machine gun firing and a cone of fire went right over the MiG’s cockpit. Ugryumov dropped his airplane about three meters down, leveled out and safely landed.

- On July 12, 1953, pilot Yulii Borisov had to make a forced landing in Andun. Do you remember that incident?

I can recall pilots Borisov, Klimov and German from our squadron, but I cannot recall the forced landing event.

- Were there any actual shoot downs over your airfield?

No, I remember how pilot Rochikashvili perished over the airfield. I was at the command post and saw an airplane coming in for landing, saw its tail number and reported that pilot Rochikashvili was on final approach. I heard him report over the radio – the speaker was on. Rochikashvili reported that he had shot an enemy airplane down, but was also wounded. The flight controller said:

“If you cannot land safely, eject.”

At about 50 meters of altitude, airplane dove and then exploded. I saw men from the ground crews running there. The airplane was torn to pieces, its wings were 20–30 meters away. The pilot’s remains were gathered in a small black bag. That same day, I was appointed to the honor guard duty and had to stand near this body bag for two hours.

A farewell assembly took place at the Dapu clubhouse the next day. Grigorii Berelidze announced that he would avenge the death of his brother-in-arms and countryman, and then Chinese and Korean pilots spoke some words. His coffin was placed on a flatbed truck, which the Chinese had covered with fir tree branches, and it set off. Later we were informed that Rochikashvili was buried on Lyaodun peninsula at the Russian cemetery in Port-Arthur, where Russian soldiers were buried in 1905, the 1930s and 1945.

301 IAP personnel

301 IAP personnel

Everything of value was sent to the relatives, of course. They were not told what had happened, with only the formal notice: “Perished on official service.”

- Did you ever cross over into Korean territory?

No, never. We had a so-called search crew, which consisted of one officer and a couple of soldiers, that drove to recover our ejected pilots or gain confirmation of enemy airplanes shot down. I was never appointed to this work.

If an American airplane went down, they gathered confirmation from local population and searched for wrecks.

- What was considered to be a confirmation?

Confirmation from the local population, what they saw at which time. This information was checked with data from gun cameras that were used to confirm firing results. Exact time and tactical number were also projected to the film. The film was about six meters in length, and immediately after landing we had to take it to the photo room.

- So, confirmation required photo proof, confirmation from local population and wrecks from crash sites?

Exactly.

- Were there cases when somebody was wounded on the ground by American strafing?

It happened in July. Vitor Buchelnikov and I went to the warehouse to get new drop tanks. We loaded them onto the truck and drove to the parking area of our 1st squadron. Our truck was going along the runway about one meter off. I was standing on the flat bed, while Buchelnikov sat in the cab with the driver. Suddenly I heard the sound of a jet engine from behind; I turned my head and I saw a Sabre dropping toward us.

I yelled:

“Stop!” and banged on the cab, and then jumped to the side. At the same time a stream of bullets went past us about 20 centimeters to the side. It lasted for a moment; the enemy airplane went straight up and to the south, toward the bay. When we examined the truck, we saw that it had not been hit by a single bullet – they all went past it, leaving marks on the runway concrete. It is good that there were no explosive bullets there, or their fragments would have ripped my head off.

It was the only case of strafing on purpose that I saw. What was surprising is that our superiors were absolutely indifferent to the fact, no reaction at all.

I have to add, that stray bullets hit one airplane’s fin, and close to it stood a tractor with the towing arm, and one bullet cut this towing arm in half. That was all the damage caused by Sabre strafing, and no one was killed or hurt. (It was not the only case. For example, on 12 July 1953 during strafing airplane of G. Berelidze was hit on the ground and damaged)

- Did you see AAA actually shoot anybody down over your airfield?

Never. I told you about the turret with NR-23 cannons, manned by Vladimir Podkolzin. There was quite strange thing: when we placed the turret at the end of the runway, Sabres would not appear over or near the airfield, but as soon as it was removed, they would be there for sure. As if they knew.

Near the airfield was a hill of about 300 meters in height, and there was a 37mm double barrel gun battery there. Once two F-86 fighters flew over Dapu airfield, and AAA opened fire on them. I saw from the side how tracers went maybe 1–2 meters above the Sabres, but didn’t actually hit them. They were a fraction of a degree off the correct aiming point. The Sabres rocked their wings and flew toward the bay.

At night, when we were at Andun airfield, B-29s flew over China, but they bombed the town Sinydzhu, which was visible over the Yalu River on Korean territory. If there was a night with bad weather, these B-29s would for sure come to bomb the town or Suphun hydro-electric generation plant. An airfield had been built for us in that town, but as soon as it was finished, the runway was wrecked by an air raid.

At nights when the bombers came, we had to wake up, run outside and hide in the trenches under mosquito nets.

I also remember that Americans dropped leaflets over our airfields printed in Russian language; they boasted that they would crush us.

There were incidents in Dapu, when at the parking area we found leaflets with a proposition to our pilots: “Fly your undamaged airplane and receive 25,000 USD.” It must have been a large sum of money back then. We gathered these leaflets and passed them to our special department officer.

- Were there night fighters at your airfield?

There were, either a squadron or regiment. We were told that it was a Leningrad regiment of night fighters. We were day fighters. We would be awakened early in the morning, and transported 3–4 kilometers to the airfield by truck. We would travel fully armed with machine guns and PPShs. After arrival at the airfield we would stack them in a pyramid and begin our usual work. In the evening, when it was getting dark, we would end our work and return to the barracks, while night fighters would take over from us. If I’m not mistaken, there was a night fighter Zaytsev, who shot down six Americans at night and was awarded HSU for that. [More likely this was Major Karelin, Anatolii Mikhailovich from 351 IAP, who was awarded HSU on July 14, 1953 for “exemplary execution of his duties as a fighter regiment commander.” 351st IAP was rotated with 298 IAP, which arrived from Leningrad area]

- Night fighters were stationed at the same airfield?

Yes, at the same airfield. But we knew little about them. Once, there was a rumor that one of them flew to Seoul and fired at ground targets at a local airfield. He was exposed when the gun camera film was developed. It was forbidden, but he was only shouted at for that.

- Could you tell us how Fisher was downed and caught? [Harold E. Fischer, May 8, 1925–April 30, 2009; shot down north of the Yalu River on 7 April 1953.]

It happened when I was working repairing my airplane after it was damaged in a dogfight. Grigorii Berelidze shot Harold Fisher down. We were working at the airplane, when we heard a MiG’s cannons rocking above our heads.

I didn’t see the maneuvering part of the fight, only heard the cannons and saw an airplane coming down with a trail of smoke. I believe that this fight took place at an altitude of about 700 meters. Usually, Sabres would sneak to the airfields at low altitude, imitate being a wingman for one of our airplanes flying alone or, preferably, obviously damaged, and opened fire at final approach. If a flight controller or other pilots warned our pilot, he usually would safely escape.

This time we saw an airplane going down, saw how its pilot ejected. Our political officer Abazin ran with a gun to his landing zone. I have read that the Chinese claimed that their pilot shot Fisher down and their ground troops captured him, but that is not true – Abazin captured him by himself. He brought the captive to some room of ours. We all gathered to look at him.

He seemed to me quite tall, of normal build, young – about 25 years old, very calm. All of his documents were taken out, including a photo of his wife and kid. We pinned all of the documents, photos and money to the wall. There were a lot of different currencies on him - yens, yuans, wongs and dollars.

Baskov - standing second at left

Baskov - standing second at left

I cannot comment on that.

- Perhaps it was due to our representative in the United Nations, Vyshinskii, who said that there are a lot of Russians with Chinese citizenship, same as Italians, Germans, and Jews with American citizenship.

Yes, there were a lot of Russians there. When we traveled to Mukden, we spoke to them, and they all the time claimed that they were about to get Soviet passports. They looked quite poor and untidy.

Let’s return to Fisher. Our regiment commander Yermakov asked him again and again: Why did his Sabre cross the Yalu River and violate the Chinese border? Thus American pilots violated the sovereignty of China. He got no answer for that. Fisher was sent to a POW camp. Two years after I returned to USSR, I read in our newspaper that Harold Fisher had been freed from Chinese captivity. (HSU Yermakov – regiment commander. Flew 65 combat missions in Korea, fought 12 dogfights, credited with 2 F-86s)

- Were there Chinese fighters at your airfield?

Yes, but only in Andun. I didn’t see them in Dapu or Mukden.

- Were you ever in Myaogou?

I was never there, but I can tell you a story connected to Myaogou.

Once we saw how our MiG was chasing an American. The Sabre flew very low and very sharp, trying to escape. I had never seen anything like that before or after. The MiG that flew after him repeated everything. Then the Sabre was hit, and dove out of our sight behind the hill, while our pilot didn’t manage the dive and flew into the hilltop. There was rumor that it was a HSU from the regiment that was stationed in Myaogou. (In a period when Baskov was in Korea only one HSU was shot down and perished – Deputy regiment commander from 676 IAP 216th IAD, Lt. Colonel Ivan Gorbunov. He was shot down on 29.06.1953г., ejected, but executed mid air by American fighters. According to art.42 of Geneva Covention amendment No1 accepted on 12 August 1949 executing bailed out crewmember in the air is a war crime. Described event could have involved Chinese or Korean pilot)

- Wasn’t the presence of so many regiments at one airfield causing mayhem, interfering with the operations?

On one side of the airfield was our regiment, on the other two – one Chinese and one North Korean. We had established a rule: Soviet airplanes flew out first, then Chinese or Koreans. Sometimes, when they took off, Americans were already there, guns blazing.

We had to hide at this moment, because stray bullets quite often flew toward us.

I remember in Dapu there was an incident, when Americans blocked other airfields, we had to receive and prepare three Soviet regiments simultaneously. They landed, airplanes were dispersed, and we begun running from one airplane to the other: guns were to be reloaded, drop tanks hung and refueled. I had to service other airplanes, too.

- How was ammo was brought to you?

By trucks, of course. In Dapu we had an American Dodge ¾-ton, Studebakers and Chevrolets.

The Dodges had sides, with seats along each which could be used by 10 men. It was a very flexible truck. We used it as a tow truck to taxi airplanes to revetments. We used them as tow trucks in Mukden and Dapu; but when we moved to Andun, the Americans got angry that we were using their equipment to fight them, and demanded that we pass them back to the US. First we had to hand over Dodges, and we got the Ural ZiS-5 as a substitute. When we were transferring to Dapu, the technical crew had to travel by ZiS-5. At the mountain roads our fully loaded truck easily overwhelmed the half-loaded Chevrolets, which caused a lot of laughter. A bit later we were completely equipped with ZiS-5s.

- What was your attitude toward American and UN forces?

We did not consider them to be UN forces – just Americans. They were the enemy.

When our airplane went down, the mood went down; if pilot perished, it was a big blow on the morale. But if we got an American – it was a joy.

- Siskov was a squadron commander?

No, he was a flight commander, but when we came back to the USSR, he was moved to the 913th regiment. There was another regiment nearby, and he was sent there with a raise. But I cannot tell you, whether he was a squadron or regiment commander there.

- What was the procedure for presenting awards?

I cannot even recall anything like that. We were simply told that that pilot got that award. And there were never special procedures.

- How did you find out that war had ended?

We knew that peace talks were going on. We understood that it was all over only when we stopped flying combat missions.

The war ended on July 27, 1953, but we remained in China until mid-August 1953. Pilots kept flying, but training missions only. When the time came, we passed our airplanes to another regiment that came in our place and later they were passed to the Koreans.

- Were there any kinds of new instruments or equipment provided for your airplanes?

There was an early warning system at the tail, which sounded a bell if our airplane was illuminated with radar. In the tail there was a secret IFF [identification, friend or foe] system. That was about everything. The gun sight was an old one.

- How many Soviet personnel were at the airfield? Including technicians, medics, and guards?

I can’t say for sure. I heard that there were about 150 men in our regiment.

At Dapu, we had a single canteen for technicians and pilots, but the ration was different, while at other airfields the canteens were different. The food was decent; I can’t complain at all.

- How did you learn of Stalin’s death?

I remember, that on March 5, 1953, we were going to Dapu airfield, and all the windows had Soviet banners in them with mourning lines attached, and we understood that something had happened. On March 8, it was announced that Stalin had died.

- As far as I understand, we had a good relationship with China before Khrushchev.

Mao used to say:

“The wind from the East is stronger than from the West!”

I remember that saying very well. Do you remember, I told you that we were met by Marshal Peng Dehuai. As I read, during the Cultural Revolution in 1960s, he was arrested by khunveibins – these were extreme-left students. He was beaten and tortured. I was outraged – how could that be? Finally it was announced in newspapers that Peng Dehuai had died in the prison hospital in 1978.

- Were there special department officers in your regiment?

Of course, there were. But I did not even know who exactly it was.

- Who was political officer?

It was Lt.Colonel Abazin.

- And Komsomol organizer?

We had special department officer and Komsomol organizer for sure, but I did not know them.

I was not a komsomol member – my grandfather was purged, I had been in jail, and thus I couldn’t pretend to be one.

And I have no idea about our medical service either – there was no need to have contact with them.

- Since you brought up medicine, were there pilots who returned to flying after wounds?

There were cases when pilots were wounded and they did return to flying and fighting. I remember there were two pilots, one short, another one tall. Forgot their names. They flew in pair, and earned a nick name “Big Pat and Little Pat.” During a training flight, they collided midair and had to eject. It was very bad situation – two airplanes were lost without any action from the enemy! They both were sent before a review board.

- Wasn’t there an attempt to write the airplanes off as if lost in combat?

No way! The pilots had to undergo a review board and were both sent to the USSR.

[These pilots were from the 1st Squadron, that is, Baskov’s squadron. Senior Lieutenant Odintsov, Nikolay Kuzmich, flight commander and pair leader; and his wingman Senior Lieutenant Stroilov, Yevgeniy. They had a mid-air collision on March 14, 1953, the details of which are contained in the book Pod Krylom Yalutszyan [Under the wing of the Yalu) Stroilov indeed subsequently was boarded and sent to the Soviet Union, but Odintsov continued his combat duties.]

- How were replacements organized?

After my arrival, no one from the technical crew was changed. Some pilots came as replacements. I can recall names: Borisov, German and Klimov.

- What uniform did the pilots wear?

The same Chinese uniform that we wore. No markings, either. They also had leather jackets for flying.

- How did you leave China?

We were loaded onto trucks, and moved to a railway station. Officers traveled separately. We crossed the border at Mansevka, and then were sent to Varfolomeevka.

- What you could have bought for the money you earned in China?

In China, I bought a suit, a flashlight and a toy for my nephew. My friend Ho Feng Ming, who spoke Russian, took me to a Chinese tailor, who made me that suit.

- On July 27, 1953, several hours before the ceasefire, Ralph Parr downed a Soviet Il-12 airliner deep over Chinese territory. All the passengers were killed. Did you know about it?

We were simply told that our airplane was shot down, with no explanation.

- Were Sabre wrecks brought to your airfield?

No. But Fisher’s Sabre fell near our airfield; it was folded up like an accordion; its wings were ripped off and the engine had broken loose.

- Were there any kinds of games of other methods of using your free time?

None at all. There was no free time to spare. I saw that Rochikashvili played a game of chess with another pilot. Then a mission was announced and game remained unfinished – Rochikashvili perished.

- How long did you remain in service after returning to the Soviet Union?

For two more years. We returned to the USSR in August 1953 and I was demobilized in 1955. But all my further life was connected to the military service.

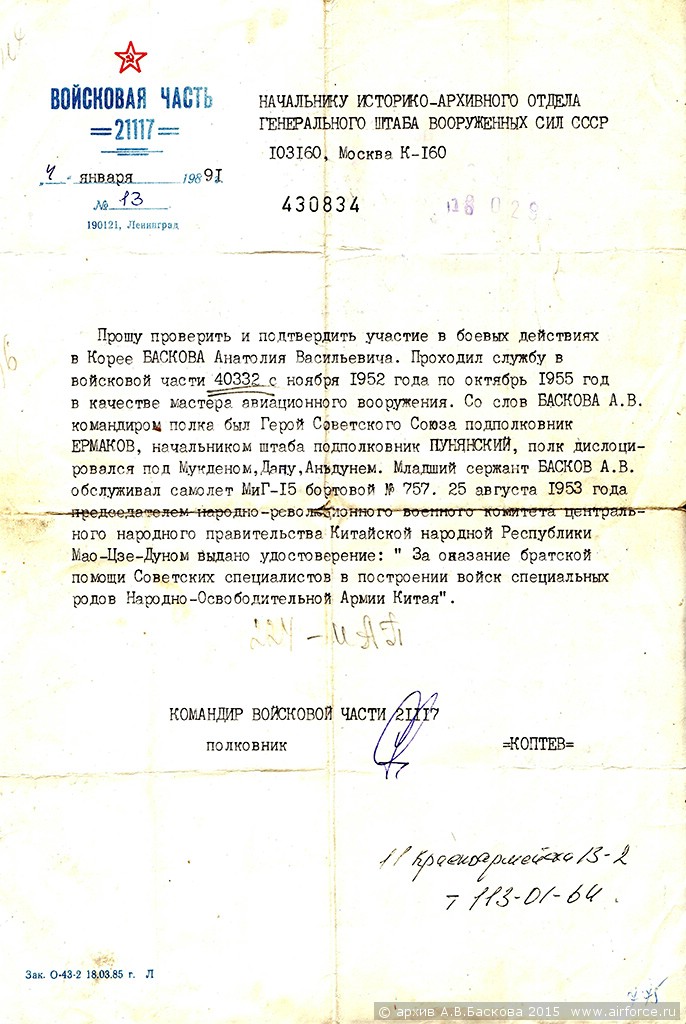

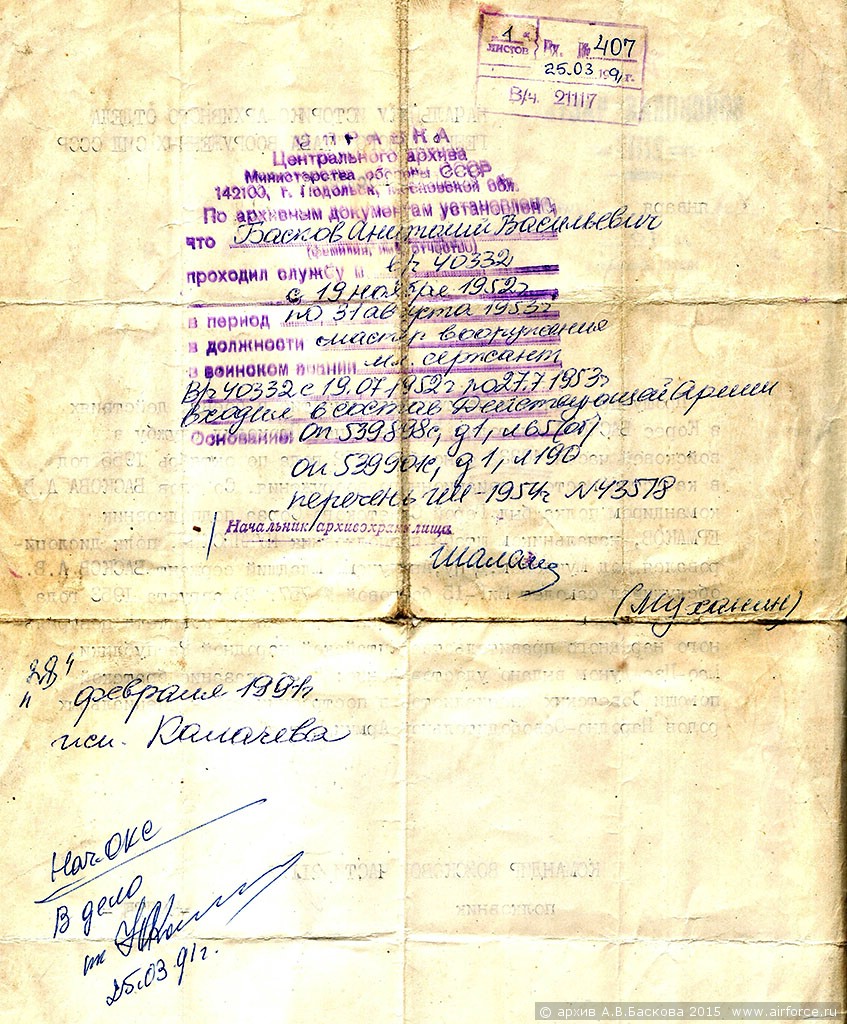

Extract from the military archive that proves A.Baskov service in Korea

Extract from the military archive that proves A.Baskov service in Korea

Oleg Korytov, Konstantin Chirkin

October 2015

Разделы сайта

Разделы сайта